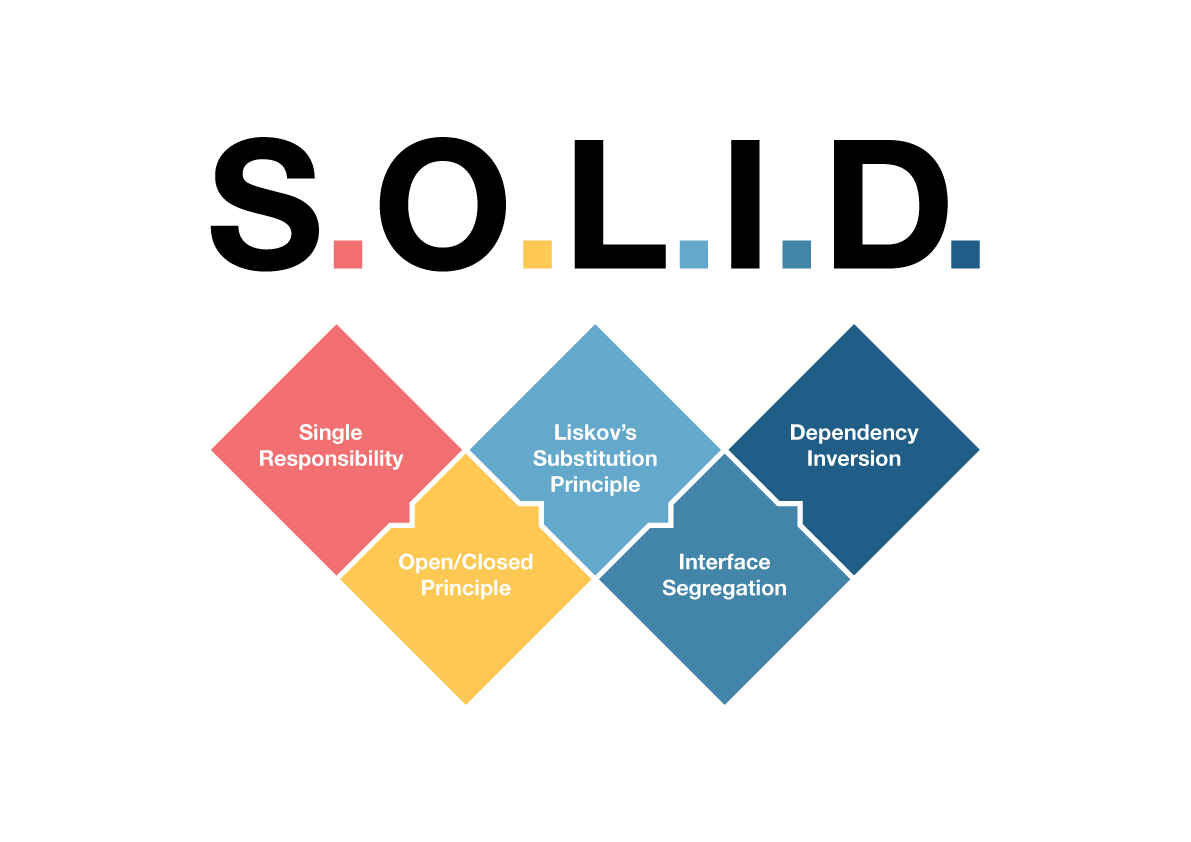

SOLID principles

1. What is SOLID principles?

The SOLID principles are a set of five fundamental design guidelines that help developers create software that is easy to maintain, extend, and understand.

Five principles are:

- The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

- The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

1.1. The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

Each class should have only one reason to change, meaning it should only do one thing or handle one specific responsibility.

Each Usecase excute a specific logic such as fetch accounts, delete accounts.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

interface FetchAccountsUseCase() {

operator fun invoke(): Result

}

class FetchAccountsUseCaseImpl: FetchAccountsUseCase {

fun invoke(): Result = TODO()

}

1.2. The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The open-closed principle states that classes, modules, and functions should be open for extension but closed for modification.

This code below violates the principle because if you want to add a new animal type, you have to modify the existing code by adding another case to the switch statement.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

class Animal(

private val name: String,

private val age: Int,

private val type: String

) {

fun getSpeed() {

when (type.lowercase()) {

"cheetah" -> println("Cheetah runs up to 130mph")

"lion" -> println("Lion runs up to 80mph")

"elephant" -> println("Elephant runs up to 40mph")

else -> throw IllegalArgumentException("Unsupported animal type: $type")

}

}

}

This way, if you want to add a new animal type, you can create a new class that extends SpeedRate and pass it to the Animal constructor without modifying the existing code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

// Abstract base class for SpeedRate

abstract class SpeedRate {

abstract fun getSpeed(): Int

}

// Specific implementations of SpeedRate

class CheetahSpeedRate : SpeedRate() {

override fun getSpeed(): Int = 130

}

class LionSpeedRate : SpeedRate() {

override fun getSpeed(): Int = 80

}

class ElephantSpeedRate : SpeedRate() {

override fun getSpeed(): Int = 40

}

// Animal class

class Animal(

private val name: String,

private val age: Int,

private val speedRate: SpeedRate

) {

fun getSpeed(): Int {

return speedRate.getSpeed()

}

}

1.3. The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Liskov substitution principle is one of the most important principles to adhere to in object-oriented programming (OOP). It was introduced by the computer scientist Barbara Liskov in 1987 in a paper she co-authored with Jeannette Wing.

The principle states that child classes or subclasses must be substitutable for their parent classes or super classes. In other words, the child class must be able to replace the parent class. This has the advantage of letting you know what to expect from your code.

Circle and Square are the implementation of Shape interface, so both them should work semlessly in place of Shape.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

interface Shape {

fun draw()

}

class Circle : Shape {

override fun draw() {

// Draw Circle

}

}

class Square : Shape {

override fun draw() {

// Draw Square

}

}

fun render(shape: Shape) {

shape.draw() // Circle or Square should work without issues

}

1.4. The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Clients should not be forced to implement interfaces they don’t use. Instead of one large interface, create smaller, more specific ones.

More specifically, the ISP suggests that software developers should break down large interfaces into smaller, more specific ones, so that clients only need to depend on the interfaces that are relevant to them. This can make the codebase easier to maintain.

Note: This principle is fairly similar to the single responsibility principle (SRP). But it’s not just about a single interface doing only one thing – it’s about breaking the whole codebase into multiple interfaces or components.

Robot should not implement eat and sleep from Worker, this is violate the ISP principle.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

interface Worker {

fun work()

fun eat()

fun sleep()

}

class Robot : Worker {

override fun work() {

println("Robot is working.")

}

override fun eat() {

throw UnsupportedOperationException("Robot doesn't eat.")

}

override fun sleep() {

throw UnsupportedOperationException("Robot doesn't sleep.")

}

}

Fix: Create three interface for each purposes: Workable, Eatable, Sleepable. And Robot will implement nesccessary interfaces.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

// Các interface nhỏ và đặc thù hơn

interface Workable {

fun work()

}

interface Eatable {

fun eat()

}

interface Sleepable {

fun sleep()

}

class Robot : Workable {

override fun work() {

println("Robot is working.")

}

}

class HumanWorker : Workable, Eatable, Sleepable {

override fun work() {

println("Human is working.")

}

override fun eat() {

println("Human is eating.")

}

override fun sleep() {

println("Human is sleeping.")

}

}

1.5. The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules; both should depend on abstractions. This principle encourages dependency injection, improving modularity and testing.

In this code, the high-level class NotificationService directly depends on the low-level classes EmailService and SMSService.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

// Low-level modules

class EmailService {

fun sendEmail(to: String, message: String) {

println("Email sent to $to: $message")

}

}

class SMSService {

fun sendSMS(to: String, message: String) {

println("SMS sent to $to: $message")

}

}

// High-level module

class NotificationService {

private val emailService = EmailService()

private val smsService = SMSService()

fun sendNotification(to: String, message: String, type: String) {

when (type) {

"email" -> emailService.sendEmail(to, message)

"sms" -> smsService.sendSMS(to, message)

}

}

}

Fix: We introduce an abstraction (NotificationSender) and let NotificationService depend on it, instead of concrete implementations.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

// Abstraction

interface NotificationSender {

fun send(to: String, message: String)

}

// Low-level modules

class EmailService : NotificationSender {

override fun send(to: String, message: String) {

println("Email sent to $to: $message")

}

}

class SMSService : NotificationSender {

override fun send(to: String, message: String) {

println("SMS sent to $to: $message")

}

}

// High-level module

class NotificationService(private val sender: NotificationSender) {

fun sendNotification(to: String, message: String) {

sender.send(to, message)

}

}

2. Pros and Cons of Clean Architecture

2.1 Pros.

Easier Maintenance: Code following SOLID principles is modular and easier to modify, as each change affects fewer parts of the app. Improved Testability: Isolated responsibilities and dependency injection make unit testing more straightforward.

Scalability: Apps following SOLID principles can grow and scale more easily, as new features can be added without disturbing the existing code.

Enhanced Readability: Clean, well-organized code is easier to understand, making collaboration and onboarding easier for new team members.

2.1. Cons

Increased Complexity: Following SOLID often means breaking code into smaller classes, interfaces, and abstractions. This can lead to an over-engineered design, especially for small projects.

Overhead in Development: Strict adherence to SOLID principles requires careful planning, design, and refactoring. This increases development time and effort.

Difficult to Learn and Apply: For beginners, understanding and applying SOLID principles can be challenging. Misinterpretation of the principles often leads to poor implementations.

Not Always Necessary: In some cases, strictly following SOLID is overkill. Small projects or prototypes may not benefit from the added complexity.